The Story of Hypnotron II

This is not a normal pinball project.

Started from a concept project in 2017, with components that trace back to at least 2013, Hypnotron II is part art piece, part tech demo, and part pinball machine.

The two project creators, Max (Maxime Damecour), also known as Space Graft and Sebastian (Zap) Zehe, are two long-time friends from Montréal and Germany, respectively. The two first met through mutual friends in the early 2010s, as participants in a small community of DIY and dance music enthusiasts. In 2013, they’d form the collaborative group Aziz! Light Crew, specializing in creating site specific installations through a combination of projection mapping, lights, and lasers, all powered by a custom software program called Freeliner.

As Max explained, “Back then, I was tinkering on these laser machines that could project kind of abstract patterns based on audio waves. And then my friend was like, ‘Hey, you should bring that to this techno party I’m doing.’ Because I had been to a rave or two, but I was like, ‘Okay, this is fun, but like it really kind of tingled my creative senses of light and movement and rhythm.’”

Max and zap both grew up exposed to location pinball in the 1990s, with fond memories of games like Terminator 2, Addams Family, and Fish Tales.

“I [zap] started out as a kid in the early 90s. We used to go camping in southern Europe and every campsite had its own little arcade back then. So there were a couple of video games, a couple of pinball games. Addams Family was around, Fish Tales was around, Terminator 2 was around. You saw those games everywhere. And I was completely fascinated by just the attract mode and blinking lights, the actual physical thing that is under the glass.”

Max added, “The first machine I ever played was Baywatch on a ferry between Prince Edward Island and Madeleine Island. As a kid my parents were, you know, a bit reserved; they weren’t going to give me quarters to go play a game. But I got to play the Baywatch game when I was very young, it must have been like ‘97 or something, barely 10 years old. And I remember there was a T2 at the airport.”

In a different universe, one where pinball didn’t almost cease to exist in the 2000s, zap is the type of pinball enthusiast who could have explored a professional career in the industry. “[As a kid] I started drawing my own pinball tables on sheets of paper and designing my own games in my head. I think when I was like 13 or 14, I built a game out of wood and wires. And it even had scoring somehow and blinking lights.”

Their parents bought them a game as a young teenager, Bally’s Silverball Mania, but it eventually stopped working, and with parts hard to come by, pinball fell by the wayside.

Neither Max nor zap returned to pinball until later in life. zap was introduced to a nearby pinball club, bought an Addams Family, started playing competitively, and repairing machines. Max, pushed by zap, grew a deeper connection to pinball by engaging with his local scene at North Star Pinball in Montréal, where he’s been playing regularly since 2016.

In 2017, the two collaborated on an unnamed prototype project, which used a 1976 Williams Dealer’s Choice, where the friends had hooked up a couple of relays and an Arduino to get coil signals from the game. Then they connected it to a program called Pure Data Sketch, which triggered Freeliner animations displayed through a projector hung on top of the game.

That project became the inspiration for what would eventually become Hypnotron II. As zap put it, “...we immediately went, ‘Yeah, we got to take this thing to where it’s an actual game.’”

A year later, work began on Hypnotron II. The video below highlights an early version of the game circa 2018.

“At one point, I had this vision of, I want to make [the Tetris Effect of pinball], where you would really sink into everything that’s going on, and there’s no specific story. It’s just sound and music matching, and the animations doing wild, wild stuff, and you kind of get lost in the game like a psychedelic experience,” said zap.

I asked if there was an elevator pitch for the game, to which Max replied, “I don’t think it’s a game for an elevator pitch. For us, we’re about doing experiments and exploring things on our own and just kind of [saying] like, hey, what’s interesting?”

Later in the conversation, we started talking about the music used in the game and the artists they worked with to create it, Superstein and RKTIC (Ronny Pries). Both have strong connections to an obscure computer art and music subculture called the demoscene.

The demoscene traces its roots back to the 1980s, when hobbyist software crackers would take credit for removing copy protection on games by creating increasingly elaborate graphics, animations, and music (called demos) using the extra disk space created by removing the code used for copy protection. Sometimes these demos would be more technically impressive than the games themselves.

Eventually, a competitive and social scene formed around this practice. At gatherings called demoparties, teams compete to create the best demos under strict technical criteria. For example, in two popular categories of competition, the 64k intro and the 4k intro, the executable file that runs the demo must not exceed 65,536 and 4,096 bytes, respectively. At these competitions, the primary glory, it seems, is recognition by your peers and the satisfaction of sharing your work with others.

As BoyC, a famous artist in the space, said in a 2012 documentary on the scene, “The point is to present a product that makes people shit themselves!”

And while Hypnotron II isn’t necessarily a direct outgrowth of the demoscene subculture, it certainly seems to share the same ethos.

I asked zap what they thought about this quote as it relates to their work on Hypnotron II. Was I on the right track?

“From my personal point of view… the goal of our Hypnotron II experiment is to showcase the possibilities that arise from the concept of mixing interactive projections with pinball while respecting the traditional concept of pinball.

Which ideally means blowing people away when they see and play the game, because it’s something they know and are familiar with, but at the same time something completely new.”

Hypnotron II wasn’t officially completed (both creators stress to me that the project never truly felt done, but they needed a stopping point) until 2024.

In between that time, it was casually brought to a few shows in Europe, where it was mentioned in places like Pinball News and a couple of forum threads, but otherwise never garnered much attention in the community.

I thought this approach was strange, but again pointed to why Hypnotron II isn’t your typical pinball project. When zap and Max first brought this game to my attention, I expected to see a lot more community discussion about the work, particularly given how mind-bending the trailer comes across and how long it’s been in development.

That it wasn’t discussed much was by design. As zap told me, “I chose to go low profile during the development, not because I was afraid that somebody would steal the idea or whatever because I never had an intention to market the thing, but because I just wanted to work on it kind of by myself and not deal with the whole pinball community, deal with the comments, and get a lot of influence from people.”

There can be almost a meditative state to producing art, where it’s not always about the final product but about the craft and the process of creating something from nothing. Sometimes the art comes from the thoughts, ideas, and emotions that reveal themselves through rote repetition. Sanding an edge till it’s smooth. Pecking at keys. Perfecting a beat.

When I asked Max about what Hypnotron II was about and the creative journey of it, he kind of alluded to the same concept, “I’d say like even in my artistic practice, I have a deep appreciation for puppetry, but storytelling is not in my wheelhouse, but like the craft and kind of expressing yourself through the craft.”

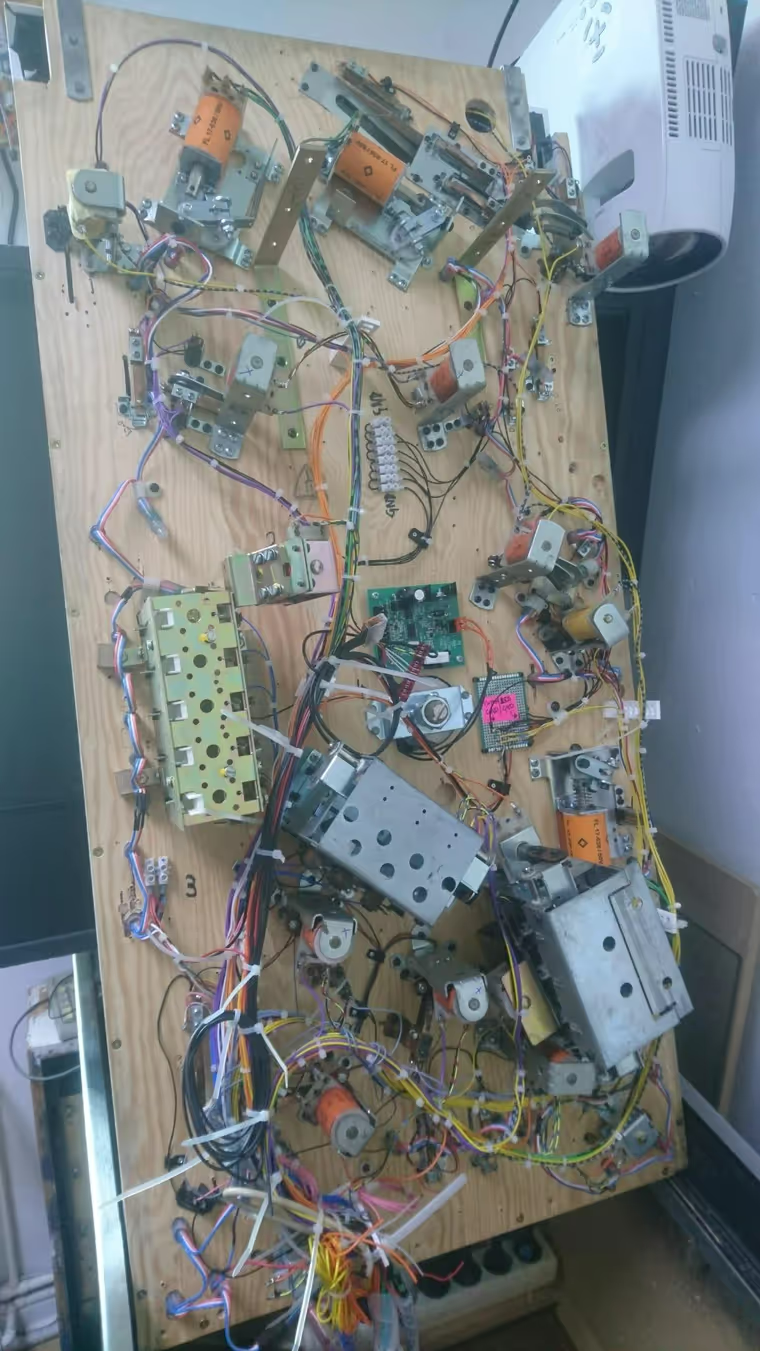

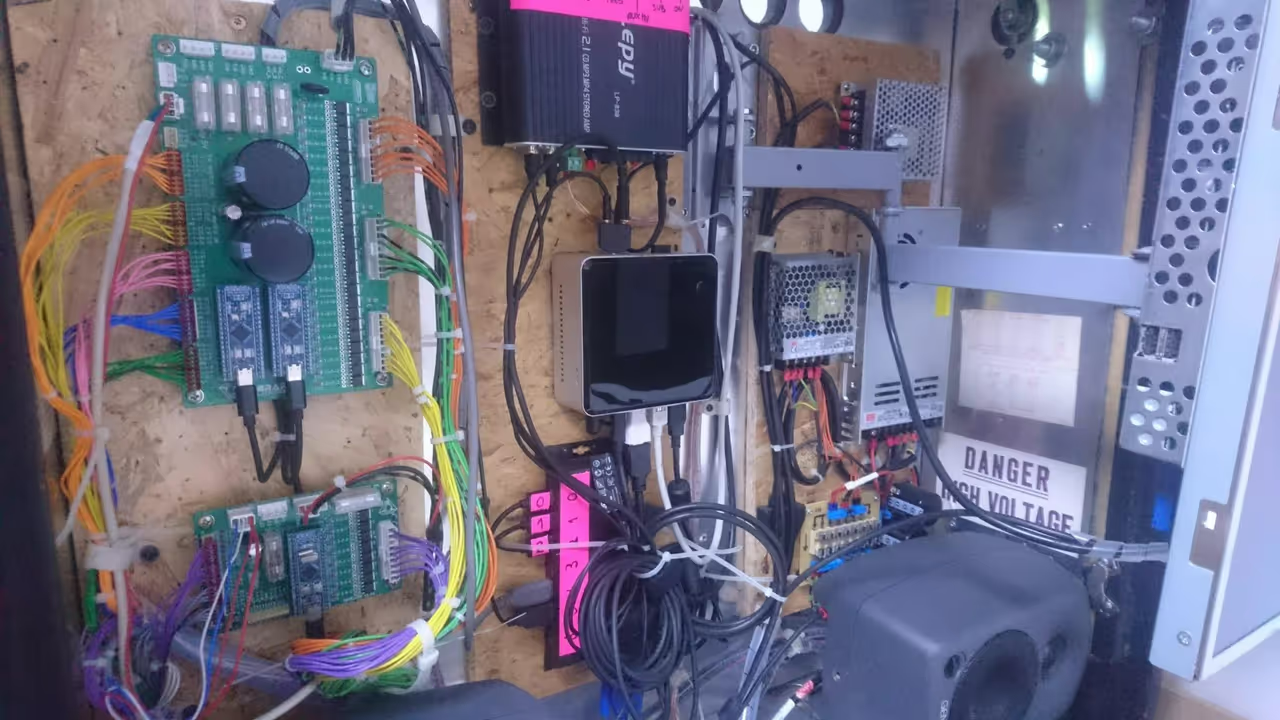

When zap described the process of building the game – purchasing an old Firepower cabinet, fashioning the playfield in their bedroom by hand, Frankenstining parts together from old games–I very much pictured a steadfast pinball monk of sorts, hunched over a workstation, slaving at a fuzzy idea of a vision only they and Max understood.

Technically, it’s a neat product. The projector is mounted above the playfield in a way that players don’t typically notice at first. As the pinball rolls around the table, it engages switches on the playfield which send signals to the custom graphics engine and changes the visuals displayed by the projector. It’s a lightweight enough engine that visuals can be altered in real time while the game is running. This graphics engine is paired with the open-source Mission Pinball Framework and various off-the-shelf or recycled components.

One major upgrade the team made just before wrapping up work was the addition of a pair of high-quality studio monitors to the backbox to give the game’s audio some punch. The game is designed to be experienced in a dark room with the sound turned up high for full sensory immersion.

Hypnotron II is more or less finished now and sitting in zap’s game room in Germany. I asked zap if they had plans to tour it around, take it to shows, and such.

“I was thinking about [Dutch Pinball Open] this year, but I’m not sure about it because I don’t think I have a lot of time to work on the game… also, it’s pretty stressful to bring a game to a show because that’s all you do during the show.”

I got the sense that the two were maybe feeling a bit of burnout on the project, even if they were excited to finally get it in front of a few more people in the pinball community. The other side of creative projects like these that people don’t always talk about is that they can be exceptionally draining for the creator. Sometimes it’s important to take a step back to refill the creative well before jumping into a new phase or taking on a new project.

“It’s like we kind of burn ourselves out doing these projects. So I think this year I’m taking it easier, I think zap's taking it easier. But you know the knack is still there. We still want to get back to it at some point.”

If the next project is anything like Hypnotron II, I can’t wait to see what might be coming next.

I’ll leave this piece with an aside from Max at a different point. It’s funny, despite working on this project for six years, he has never had it in his hometown for any period.

“Damn, I hope we can bring the game to Montréal at one point. It’s always been a dream.”

Maybe the pinball community can do something about this?