1990 was a turning point year for pinball in more ways than one. Data East was beginning to make their presence known with tables based on some of the most iconic licenses of the time, and beginning to develop a dot-matrix display system that would revolutionize pinball for the following three decades; and Williams & Bally were beginning to create a wider variety of tables targeted towards both casual and advanced players, with FunHouse giving them a ton of attention at the end of the year.

Gottlieb, however, hadn’t quite seemed to catch up with the competition. While a lot of their late 80s tables such as TX-Sector, Diamond Lady, and Bad Girls are still good tables and ones I always look forward to playing, they didn’t seem to strike a chord with operators or players at the time. Operators wanted machines that were easy to maintain and could earn more consistently than their prior tables, and to answer this demand, Gottlieb looked to the future by looking to the past of pinball design.

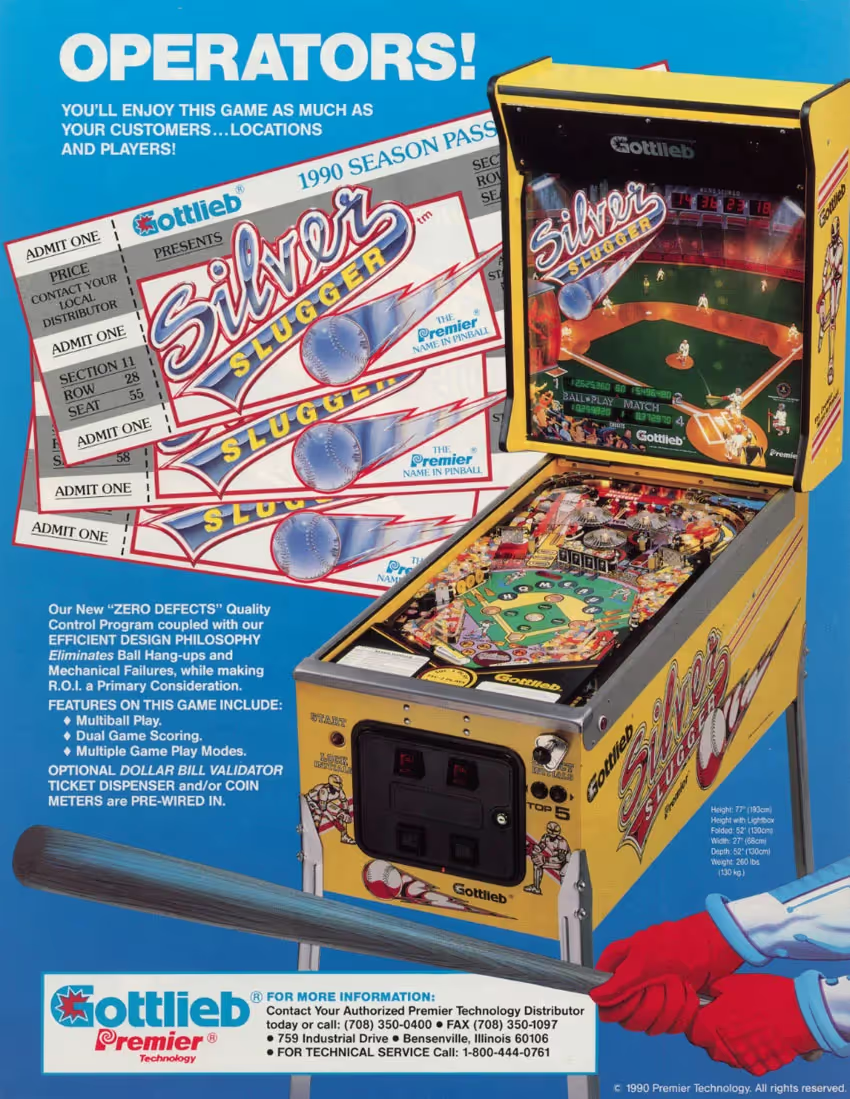

Silver Slugger

Gottlieb’s ”street-level” idea was designed with the concerns of these operators at the forefront, being more mechanically simple games with no ramps and an increased focus on target banks and loop / orbit shots. In some ways, these designs called back to older Gottlieb tables from the 70s and 80s, both in their playfield layouts and overall theme sensibilities. Their first street-level pinball machine was Silver Slugger, released in February 1990 and designed by John Trudeau.

Silver Slugger has a classic baseball theme designed with enough depth to bring in players who might be looking for something more, but at its core, it’s an incredibly aggressive table best suitable for advanced players. The player advances the ballplayers through the baseball diamond by completing drop targets, shooting the vari-target, spelling WALK at the top lanes, or shooting the saucers for home runs & mystery awards. This game has some truly addictive orbits, which will become a common theme across the Gottlieb street-level machines; the standout shot on this machine is the right orbit which sends the ball flying to the left flipper and awards a jackpot when hit multiple times in a row. Not a bad first attempt from Gottlieb here, and though I’ve had minimal time on this table, I always look forward to playing it.

Operators seemed to agree, as Silver Slugger sold the highest of the six Gottlieb street-level machines with a total of 2,100 units sold, selling about as well as many Williams or Data East tables of its era did. However, Gottlieb would go on hiatus after releasing their first street level table. When Gottlieb returned to releasing new tables later in 1990, the pinball landscape had substantially changed, reducing people’s interest in these street-level designs.

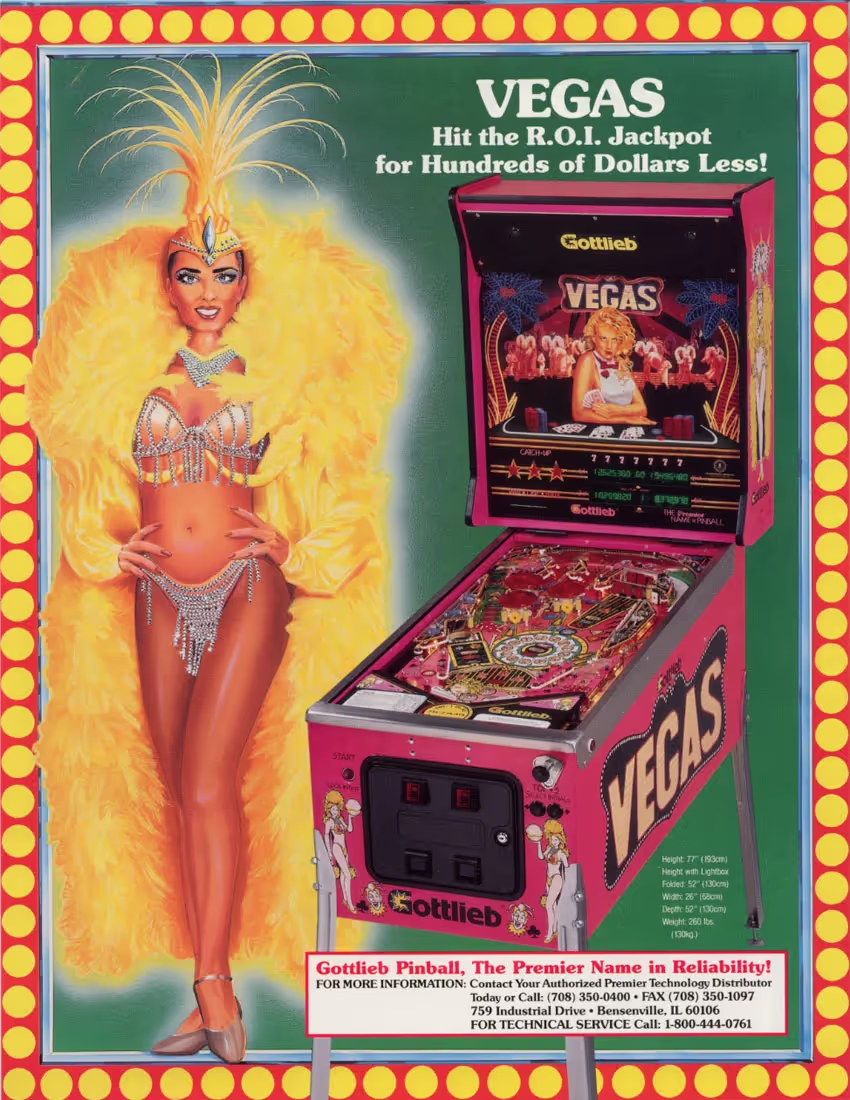

Vegas

Designed by Jon Norris and released in July 1990, Vegas can be considered a spiritual successor to a practice Gottlieb engaged in in the 1980s where they looked back to their past tables and revitalized them with updated graphics and audio (see: Excalibur vs. Count-Down). In this case, Vegas heavily takes after Gottlieb’s 1978 classic, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, complete with an electronic take on that game’s roto-target at the top right of the playfield and drop targets in a very similar position.

Vegas is a casino-themed game with emphasis on target sharpshooting. The roto-target at the top right awards points based on the displayed number and lights that number on the “casino wheel” on the center of the playfield; the yellow targets add letters to VEGAS and eventually light the cashier target near the roto-target for big score; and both the roto-targets and a “bumper shot” into a top lane collect jokers and qualify select-a-feature at the game’s left saucer. Typical for a Gottlieb table, Vegas also includes a left orbit that can be easily repeated thanks to how Gottlieb flippers are designed and can be multiplied up to 5x to award 5 million per shot. The loop millions tend to distract from what the rest of the table is going for, giving the table’s rules a bit of an identity crisis; but Vegas certainly looks visually striking, with its hot pink color palate sure to contrast with other machines near it.

Vegas sold slightly less units overall than Silver Slugger, just about 1,500 units. Jon Norris wouldn’t give up on the casino idea after this table; when he worked at Stern he would design a table called High Roller Casino, with code support from Keith Johnson, that took a few cues from this table including a slot machine mechanic very similar to the one on Vegas.

Deadly Weapon

Released in September 1990 and designed by both Trudeau & Norris, Deadly Weapon is a machine that I would describe as being a great table released at the wrong time. The table released in the same month as Data East’s The Simpsons, which released to the accolades of the AMOA and had an iconic theme to back itself up – and had way more units produced. Deadly Weapon was comparatively another Gottlieb “original” theme loosely based on the first Lethal Weapon film, but where it lacks in theme originality, its layout completely makes up for and then some.

Deadly Weapon shares a lot in common with Silver Slugger in that it has a lot of focus on orbit shots and less focus on targets. The main rule of the game resembles that of Victory; in that game, the player completed checkpoints for hurry-ups in a strict order, and here, the player completes arrests in a similar fashion. Many of the shots on this game require strong flippers, as they pass through the playfield into saucers that can’t be hit directly. The game also has one of the best multiballs of its era; started via a mystery award, collecting jackpots is as simple as completing all the arrests during multiball, though this is easier said than done. Helping the game’s unique layout is an upper flipper designed to hit the lane on the right and graze off the upper drop targets and lower standup targets.

Deadly Weapon had the lowest production run out of any street-level so far, with only 803 units being produced, and I’m inclined to believe that this was due to The Simpsons taking up a lot of operators’ attention at the time. However, in retrospect, I view Deadly Weapon as the better table, and this seems to be the case with current pinball designers as well; the right lane placement on this table helped inspire the similar placement of the tail whip lane on Stern’s Godzilla, and the unique left return lane on this table also made a comeback very recently on Stern’s The Uncanny X-Men. Though it might not have been appreciated in its time, Deadly Weapon is getting more than the love it deserves nowadays and I’m very happy that it’s finding an audience.

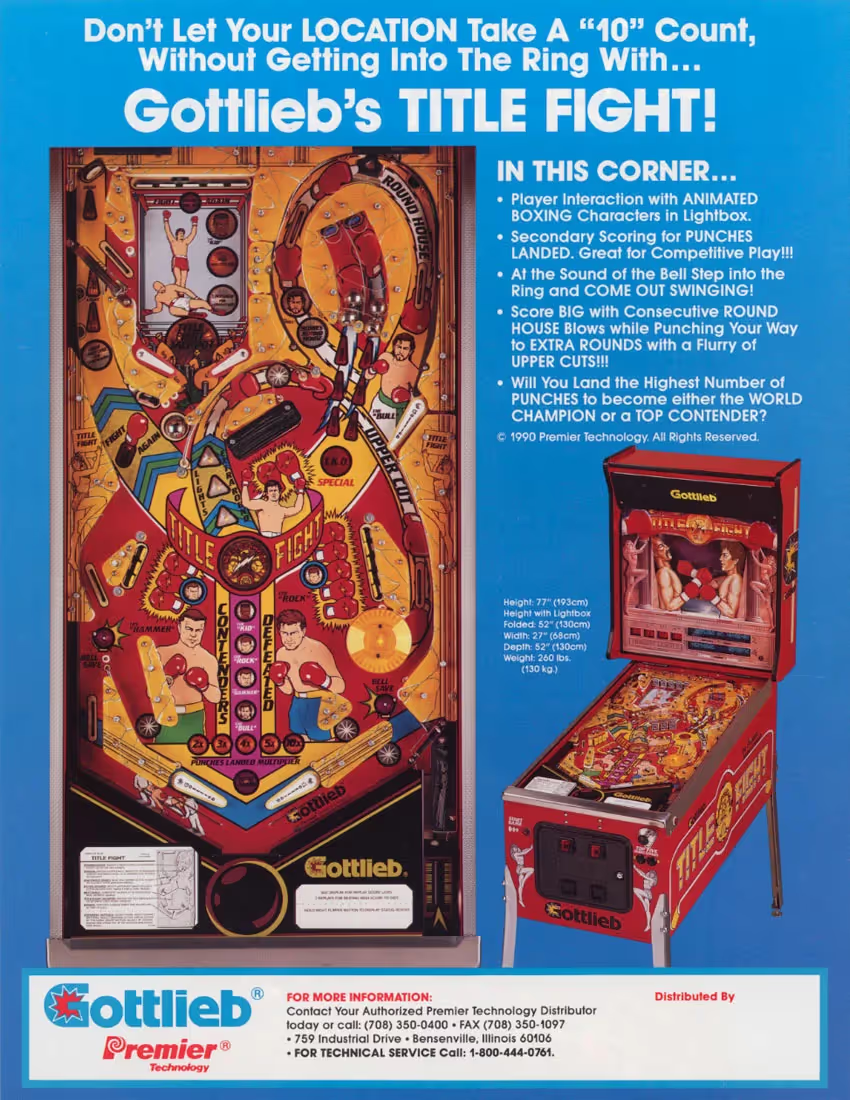

Title Fight

Title Fight, I unfortunately feel less positively about, and honestly runs contrary to what the street-level tables were made for in my opinion. Unlike the past three tables that lived and died on their layouts alone, Ray Tanzer’s Title Fight relies heavily on two gimmicks: the mini-playfield with a 5-bank of drop targets, and the animated backglass used for mystery awards. Released in October 1990, just a month before Williams’ FunHouse, this table had very little time to impress operators, though it still has its moments.

Title Fight is a boxing themed table. At the start of each ball, and during balls by shooting the left target to “ring the bell”, the player access the mini-playfield and must complete five drop targets; after which the ball falls into the saucer and the player must time their punch on the mechanical backglass to score a mystery award. The game otherwise relies on an average mix of drop targets and loops, with the biggest source of scoring being the roundhouse loop at the top right which can be repeated for increasing points on every shot. Defeating all four contenders (three drop target banks and the roundhouse loop) will enable title fight jackpot if the player can complete the drop targets again.

Sales for Title Fight were slightly higher than those for Deadly Weapon with a total of 1,000 units sold. While the game has a very friendly design for newcomers, giving every player easy access to the mini-playfield and mystery awards with minimal pinball knowledge, I unfortunately feel that this design harms the table in the long run rather than adds to its appeal. I also feel that the street-level designs weren’t really made with these kinds of gimmicks considered that were more common on their prior tables. While Title Fight is my least favorite street-level table, I can’t lie: I still have fun shooting that roundhouse loop and I like how the inlanes are designed on this table, very unique and befitting of a street-level design.

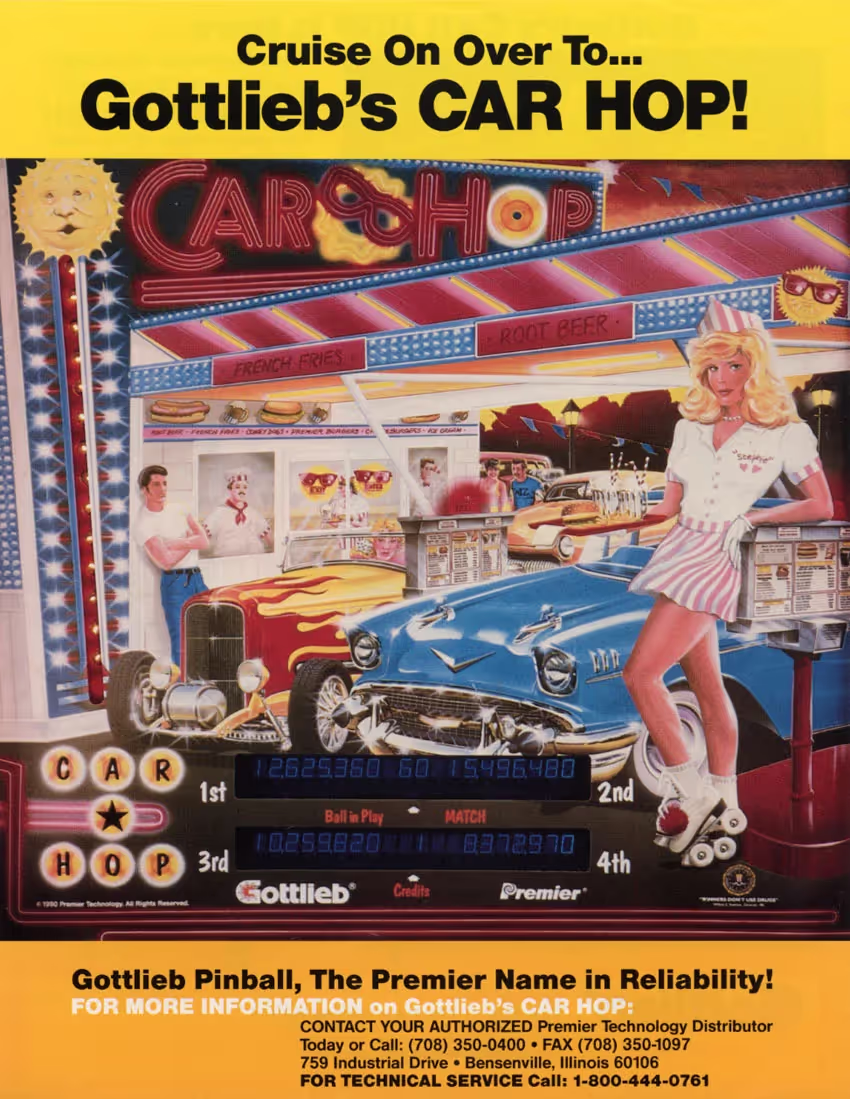

Car Hop

Compared to Title Fight which was trying to be a “modern” table on a street-level budget, Car Hop goes for a different approach; a modern-looking table with sensibilities of a classic table and a classic 50s theme. Jon Norris’ second and final street-level table was released in January 1991 and thankfully was released in a bit of a “dry spell” for new pinball machines, though FunHouse still had the attention of players and operators, making these street-levels continue to be a hard sell.

Car Hop is a simple game all about drop targets and orbits. Completing the drop targets, shared between the left and right sides of the playfield, awards the flashing ice pop and awards whatever is listed on the ice pop (points, extra ball, or special rounds, or adding to HEAT or WAVE). The game also features a bullseye target in the center which requires precise hits to register, and an addictive combo involving shooting the right loop into the single drop target, into the left spinner, which is where the biggest and most reliable points on the game come from. The game’s simplicity is compounded by offering a “nostalgia mode” featuring reduced points values and eschewing the audio for exclusively classic EM-styled chimes.

Simple doesn’t necessarily mean bad and Car Hop is proof of that, though it only sold a few more units than Title Fight overall (1,061). While not my absolute favorite street-level table, the combo potential with the loops as described above make this a fun one to play and even watch as was demonstrated at INDISC a few months ago. The table’s layout would later be reused for another Jon Norris design, World Challenge Soccer, and the influence of its layout can still be felt today on Stern’s King Kong: Myth of Terror Island, which places its river shot and punchback target in very similar positions to the right loop and drop target on Car Hop and encourages a similar combo flow.

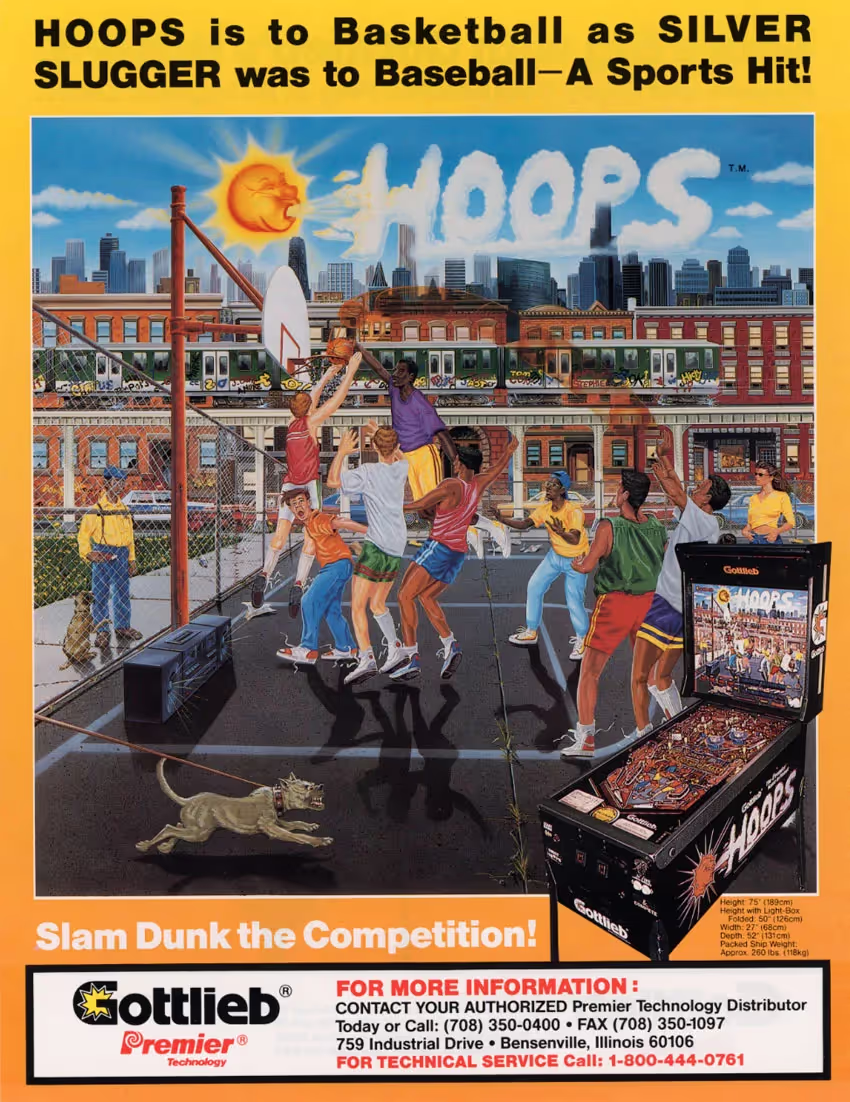

Hoops

If you’ve read this site recently you may know how I feel about Hoops, but if you haven’t, just know that this is one of the tables I did a tutorial for and that should let you know my thoughts on it. Hoops is the final Gottlieb street-level table, released in February 1991, and was designed by Ray Tanzer with the intent of making a game that brought to basketball to pinball in a similar fashion to how Silver Slugger combined baseball with pinball. Tanzer did an admirable job with this final layout with high emphasis on orbits and saucers rather than targets, and like Deadly Weapon before it, is a table I always look forward to playing.

Hoops is an easy-to-learn game - shoot either “lock ball” saucer to start multiball and then lock both balls during multiball to collect super slam – but the game’s addictive nature is all in its difficulty and finding ways to best handle the feeds from the game’s three different saucers. The game also accounts for basketball scoring by giving basket points for every saucer shot and awards these basket points in bonus at the end of the game (so long as the player doesn’t tilt). Combine these simple rules with a “hang time” bonus built up at the bumpers and spinners and collected at either the lit captive ball or at the end of each ball and you have a table that’s simple but incredibly fun and addictive to try and get high scores on.

Sadly, Hoops was the nail in the coffin for the Gottlieb street-level designs, selling only 879 units. I have a few theories on why Gottlieb may have quickly reverted to standard pinball design that I’ll discuss following my thoughts on Hoops, but it’s a shame that their legacy had to end here as Hoops is an outstanding note to go out on. The game’s multiball is simple but incredibly addictive, and Keith Elwin would revitalize the idea when he designed James Bond 007 60th Anniversary with a multiball that I enjoy even more than this one. While not my favorite table designed by Ray Tanzer, this is my favorite one that he designed by himself.

My Street-Level Ranking

From best to worst:

- Deadly Weapon

- Hoops

- Silver Slugger

- Car Hop

- Vegas

- Title Fight

What Killed the Street-Levels?

For years the answer has been as simple as “they didn’t sell”, but I have three theories on why Gottlieb began to move away from this design philosophy:

- FunHouse and The Simpsons both did a number on potential sales of the street-levels. While both machines were costly to maintain, they contained two aspects that the street-level Gottlieb machines lacked: unique mechanics and iconic themes respectively. Both released in late 1990 and reduced the sales of tables like Deadly Weapon and Car Hop that could’ve found a following had they released slightly earlier in “dry spells” for new releases.

- Pinball was changing. There’s a chance that Gottlieb could’ve caught wind of Data East’s plans to introduce the DMD, and their first DMD table, Checkpoint, released in the same month that Hoops did: February 1991. Though Data East beat Williams to the punch, Williams would wind up releasing their first DMD tables later that same year with Gilligan’s Island and Terminator 2: Judgement Day. Gottlieb might have felt cornered by the two companies and wanted to transition into DMD tables by returning to their “classic” design philosophies first.

- Bally’s own attempt at a “street-level” design with Harley-Davidson had minimal returns. The table wasn’t what a lot of players expected from the Williams / Bally name and was one of their weakest selling releases, especially in a year that introduced some of the highest selling tables of all time. Seeing early sales of the table might have also convinced Gottlieb to put an end to this design philosophy.

While the Gottlieb street-level tables were short lived, only lasting just over a year, I’m glad that designers like Keith Elwin and Jack Danger have continued to recognize their impact and designed tables that take after their layout sensibilities.

Experimenting with playfield layouts might increase the learning curve of some tables, but also helps us expand our knowledge as players and learn new techniques we might not have known before. Gottlieb might have intended for their street-level tables to be operator friendly, but nowadays they’ve found a following for having innovative playfield layouts years ahead of their time.

The Gottlieb street-levels are proof that one’s work might not be appreciated when it releases, but will always find an audience with time no matter what.

.avif)